Q. Hello. In a book for publication in the US, we are citing a British-published book with single quotes in the title: Julie Hankey, A Passion for Egypt: Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the ‘Curse of the Pharaohs.’ Do we change them to double quotes, per US usage? My instinct is to leave it alone, but I want to follow CMOS guidance.

A. CMOS considers the form of quotation marks, whether double or single, to be an arbitrary decision that’s subject to being adjusted to conform to the style in the surrounding text. We’d accordingly change the quotation marks in the Hankey title from single to double to match the usage in a document that follows Chicago (or US) style.

We’d similarly adjust quotation marks in a direct quotation—for example, from single to double in a block quotation of a passage that includes single quotation marks or from double to single in a passage that includes double quotation marks that are themselves quoted with the use of double marks. Such adjustments are at the top of the list of permissible changes at CMOS 13.7. Much of that list would apply to titles of works (but see CMOS 14.88).

We’ll try to clarify this in a future edition of CMOS.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello! How does one cite a pamphlet included with a DVD? The pamphlet contains a short essay which has an author but no title. Thank you!

A. Let’s say your text says something like this: “In a booklet accompanying the twenty-fifth-anniversary DVD of Name of Film, So-and-So wrote . . .” Then you would cite the DVD (see CMOS 14.265 for examples).

But because you’ve already mentioned the booklet (the usual word for such an insert) in the text, there’s no need to add it to a citation in a note. If that’s not the case, you can add the word “booklet” to the end of the note. It could also be added to any bibliography entry for the DVD (e.g., “Accompanied by a booklet with an essay by So-and-So”).

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. I coordinate blind peer review for an academic journal that deals with the humanities and the sciences. Often reviewers recommend to the authors a clearer way to phrase the authors’ ideas. Some authors worry that adopting the reviewers’ exact wording would be plagiarism, but when these authors try a brand-new phrasing, I find it has the very problems the reviewer wants fixed. I’m inclined to think that, if something is published in a peer-reviewed journal, one should assume that matters like phrasing (and discovery of sources and objections) will include some contributions from reviewers, but what advice should I give scrupulous authors? Thank you.

A. Authors routinely implement suggestions from their copyeditors on how to phrase a particular idea for maximum clarity and effectiveness. A similar suggestion from a peer reviewer would fall into roughly the same category. Neither scenario would constitute plagiarism.

Still, authors should acknowledge their debts to others for any idea that isn’t purely trivial. A suggestion from a peer reviewer can be credited in a note—for example, “The author would like to thank an anonymous peer reviewer for raising a key objection to her initial hypothesis and for suggesting the phrase ‘biometric apparition.’ ”

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello, I use old-style figures in the text of my document. Do you have any recommendations for whether they should then be used also for footnote markers in the body text and/or the footer?

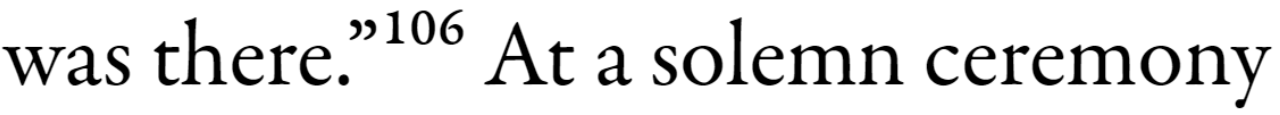

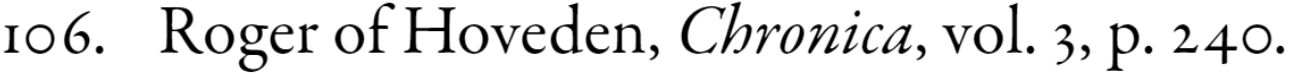

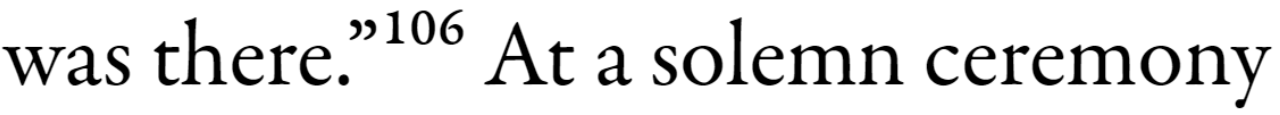

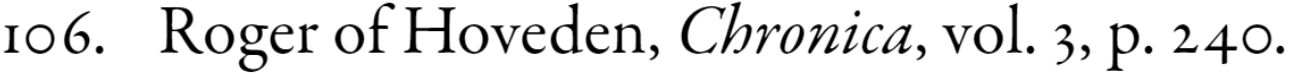

A. Our designers prefer lining figures for the superscript note reference numbers in the text, even in works that otherwise feature old-style figures—as in the book Eleanor of Aquitaine, as It Was Said: Truth and Tales about the Medieval Queen, by Karen Sullivan (University of Chicago Press, 2023). The corresponding numbers at the beginning of each note, however—which in Chicago style aren’t superscripts—would use old-style figures.

Superscript lining figures in the text:

01.2023-10-20-12-08-14.png)

Old-style figures on the baseline in the corresponding note:

01.2023-10-20-12-09-51.png)

Notice how the digits in the superscript 106 are all roughly the same height, ensuring that a note number 1, for example, will be about the same size as a note number 6. This matters more with the smaller superscripts than it does for the numbers that sit on the baseline—even in the text of the notes, which is slightly smaller than the main text. (The Sullivan book features endnotes, but the advice would be the same for footnotes. See also CMOS 14.24.)

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Have we abandoned altogether the rule to put note reference numbers (and only one per sentence, please) at the end of the sentence? I’ve prepared indexes for a number of academic monographs lately where note reference numbers are sprinkled willy-nilly throughout the text.

A. CMOS does still say that a note reference number1 is best placed at the end of a sentence or clause,2 but there isn’t any limitation—technical or otherwise3—that might prevent authors from placing such a reference4 elsewhere, or that might bar authors from using more than one in a sentence.5

So if a publisher or editor has failed to enforce the spirit of CMOS6 relative to note reference numbers—and the book’s already at the indexing stage7—there’s not much we can do to help you.8

__________

1. Or symbol—*, †, ‡, etc.

2. See CMOS 14.26.

3. A note reference number can literally appear anywhere in a document.

4. Like this one.

5. This sentence has five.

6. See note 2 above.

7. As described in CMOS 16.108.

8. Other than show with this answer how distracting such notes can be. :-)

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. In a collection of (some previously published) essays all by one writer, does one cite the author as the editor too? CMOS 14.104 and 14.106 seem to come close, but they don’t address this exact situation. In the source I’m working with, the title page does not credit the author as editor, but some of the essays were previously published. Thanks!

A. No, you wouldn’t cite the author as both author and editor of the book. For example, “The Girl in the Window” and Other True Tales (University of Chicago Press, 2023) is an anthology of stories written by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Lane DeGregory that were originally published in the Tampa Bay Times (formerly the St. Petersburg Times).

The title page credits DeGregory as author of the book and Beth Macy as author of a foreword. No other contributor is listed. So even though it was DeGregory herself who compiled, edited, and annotated the stories, you wouldn’t cite her as editor also.

Besides, the words “edited by” don’t have the power to tell the reader that some or all of the essays in a book were previously published. If that info is relevant, you can say so either in the text (as we’ve done near the beginning of this answer) or in a note. But for the citation itself, follow the title page.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. Hello! Here’s a fun citation style question: How do you cite website content that’s accessible only through the Wayback Machine from Archive.org?

A. Cite the content as you normally would, but credit the Wayback Machine and include the URL for the archived page. For example, let’s say you were to mention the fact that Merriam-Webster.com still listed the hyphenated form e-mail in its entry for that term as late as January 2, 2021, with email offered as an equal variant (“or email”). You could cite your evidence in a footnote as follows (see also CMOS 14.233):

1. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “e-mail,” archived January 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20210102004146/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/e-mail.

Notice the URL, an unwieldy double-decker consisting of two consecutive URLs stitched together. If you wanted a shorter URL, you could cite only the second part (i.e., the original URL for the content), as follows:

1. Merriam-Webster, s.v. “e-mail,” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/e-mail, archived January 2, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

That’s a bit more concise than the first example, but readers will need to enter the original URL at the Wayback Machine (which they’ll have to find on their own) and then use the date to get to the right version of the page.

Either approach is acceptable as long as you’re consistent.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. If a run-in quotation ends with a question mark or exclamation point, is a period needed following the parenthetical source? For example: The girl in the novel asked, “Where’s Toto?” (Baum 1939) Could you also direct me to the section and examples in CMOS 17? Thanks in advance for the help!

A. Yes, you need to add a period after the closing parenthesis, but only if the quotation is presented in line with the rest of the text (as in your question).

For example, you might quote Dorothy asking the Lion (capitalized in the original) not to bite her dog: “Don’t you dare to bite Toto!” (Baum 1900, 67). Note that we’re referring to the original 1900 edition of the L. Frank Baum classic (published by the George M. Hill Company). And note the period after the parenthetical citation.

But if you present the quotation as a block, there’s no period after the source:

“Don’t you dare to bite Toto! You ought to be ashamed of yourself, a big beast like you, to bite a poor little dog!”

“I didn’t bite him,” said the Lion, as he rubbed his nose with his paw where Dorothy had hit it.

“No, but you tried to,” she retorted. “You are nothing but a big coward.”

“I know it,” said the Lion, hanging his head in shame; “I’ve always known it. But how can I help it?” (Baum 1900, 67)

See CMOS 13.69 and 13.70, respectively. And don’t forget about search. If you enter the words “source period parentheses” in the search box at CMOS Online, you should get those paragraphs among the top results.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. If sixteen articles were published under the same title across sixteen consecutive issues of a periodical, and the author wishes to represent them all in a single reference, how would you suggest formatting the footnote?

A. When a source citation gets complicated, try adding a description. If the sixteen articles appeared, for example, in an academic journal published in annual volumes with four issues each, you could do this:

1. Author’s Name, “Title of Article,” Name of Journal, vol. 72, no. 1–vol. 75, no. 4 (2016–19); published as a series of sixteen articles under the same title.

Though “vol.” is normally omitted in Chicago-style citations for journal articles, it may be retained as needed for clarity (as in the example above).

Another approach would be to cite the first article, as follows:

1. Author’s Name, “Title of Article,” Name of Journal 72, no. 1 (2016), https://doi.org/ . . . ; continued as a series of sixteen articles under the same title through vol. 75, no. 4 (2019).

The second option has the advantage of allowing for a DOI for the first article, which should help readers track down that article and, from there, the rest of the series (see also CMOS 14.8).

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

Q. In CMOS 14.160, you recommend citing reflowable electronic text using “a chapter number or a section heading or other such milepost in lieu of a page or location number.” Should the section heading be labeled “section” to show that it is intended as a location?

A. The key word is “under,” and in a book with chapters it’s helpful to add a chapter number in addition to a section title. For example, the EPUB edition of Matthew Shindell’s For the Love of Mars could be cited in a note as follows:

1. Matthew Shindell, For the Love of Mars: A Human History of the Red Planet (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023), chap. 4, under “The Nineteenth-Century Cosmic Epic,” EPUB.

2. Shindell, Mars, chap. 5, under “Mars after Detente.”

But it’s usually better for your readers if you cite specific pages in books (partly because books are so long). If you have the option of consulting a print or PDF edition of a book, do so, and then cite by page number.

[This answer relies on the 17th edition of CMOS (2017) unless otherwise noted.]

01.2023-10-20-12-08-14.png)

01.2023-10-20-12-09-51.png)